Exhibition Foreword

The United States of America is frequently described as a “nation of immigrants,” and the reasons for immigration are diverse – the search for better economic opportunities, the escape from persecution and pursuit of sanctuary, or to reunite with family or loved ones.

Today, almost 90 million immigrants and individuals with Chinese heritage live in the United States. Making In Between: Contemporary Chinese American Ceramics highlights the work of six, first- and second-generation Chinese-American ceramic artists. The works of these artists share themes of cultural heritage, identity, language, politics, migration, and displacement. While their works are unmistakably individual, they share a rich heritage shaped by their American and Chinese experiences.

Many artists mine their cultural heritage for artistic content, artists who are immigrants (or the children of immigrants) can uniquely explore the connections and disjunctions between two or more cultures. Sin-Ying Ho uses traditional production techniques and processes learned in Jingdezhen, China to produce works on which she marries traditional Chinese imagery with stock market tickers and other emblems of contemporary New York life. Stephanie H. Shih crowdsources food images from online diaspora communities and reproduces them in a trompe l’oeil style. Both use their art to build bridges and forge connections across borders, places, and time.

The theme of identity also presents privileges and burdens for artists working in this arena. Throughout history, nations have reacted to influxes of migrants with laws and policies aimed at preserving privilege, preventing immigration, and maintaining the status quo. The history and legacy of these policies and continuing cultural biases can be seen in the way that artists like Cathy Lu, Beth Lo, and Jennifer Ling Datchuk tackle themes of otherness, isolation, and struggle.

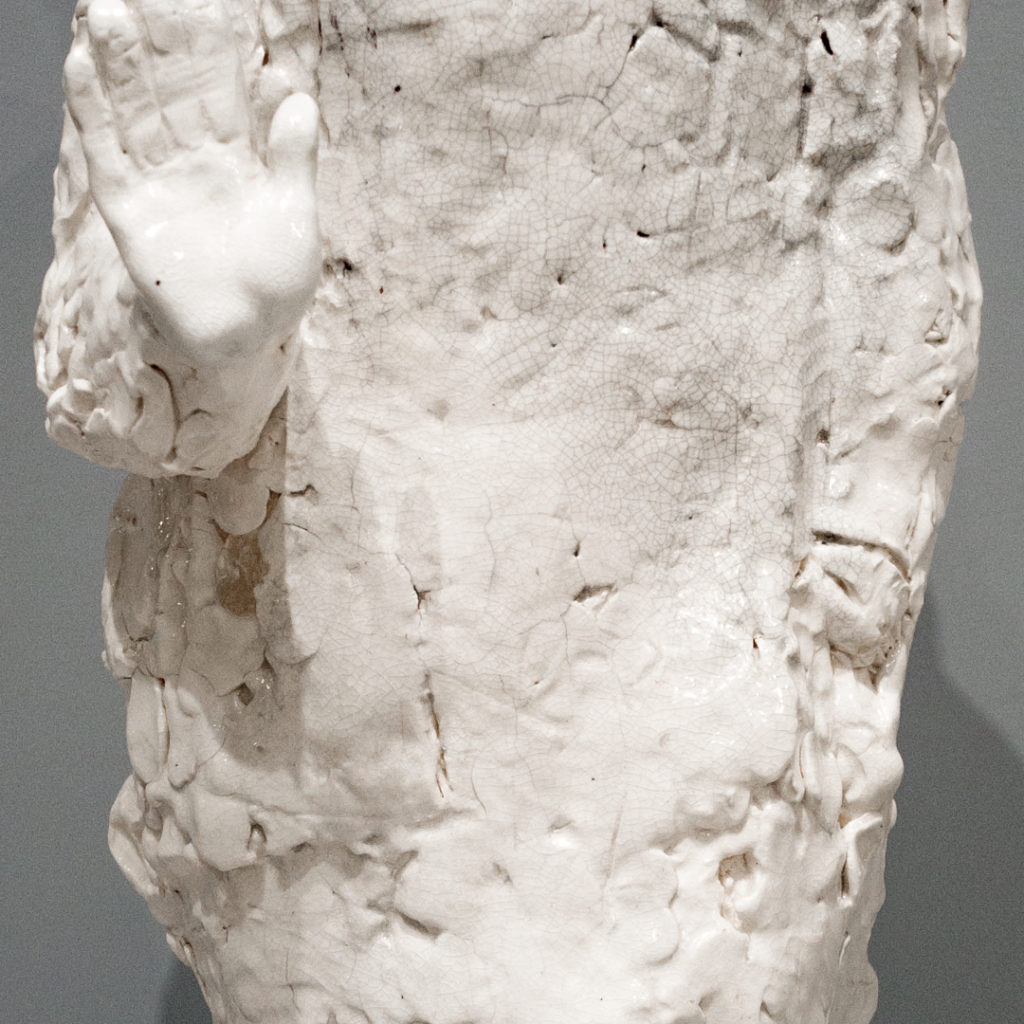

Political considerations, especially for first-generation immigrants, can be as inescapable as it is inspiring. Ai Weiwei, perhaps the most well known contemporary Chinese artist expatriate in the 21st century, has made waves outside of traditional art circles for the political critiques embedded in his works. Works in this exhibition by Wanxin Zhang lend themselves to this tradition, whether explicitly through busts of Mao Zedong, or implicitly through cultural iconography. Zhang makes the case that his art cannot be considered in isolation from the politics of his past.

Immigration and the global movement of people continues to be a divisive topic. Despite this, people with diverse histories and heritages have driven, and continues to drive, artistic production and innovation. Our cultural fabric has been enriched by the contributions of the artists in this exhibition, and the countless others that have come to call the United States their home.

Beth Ann Gerstein, Executive Director

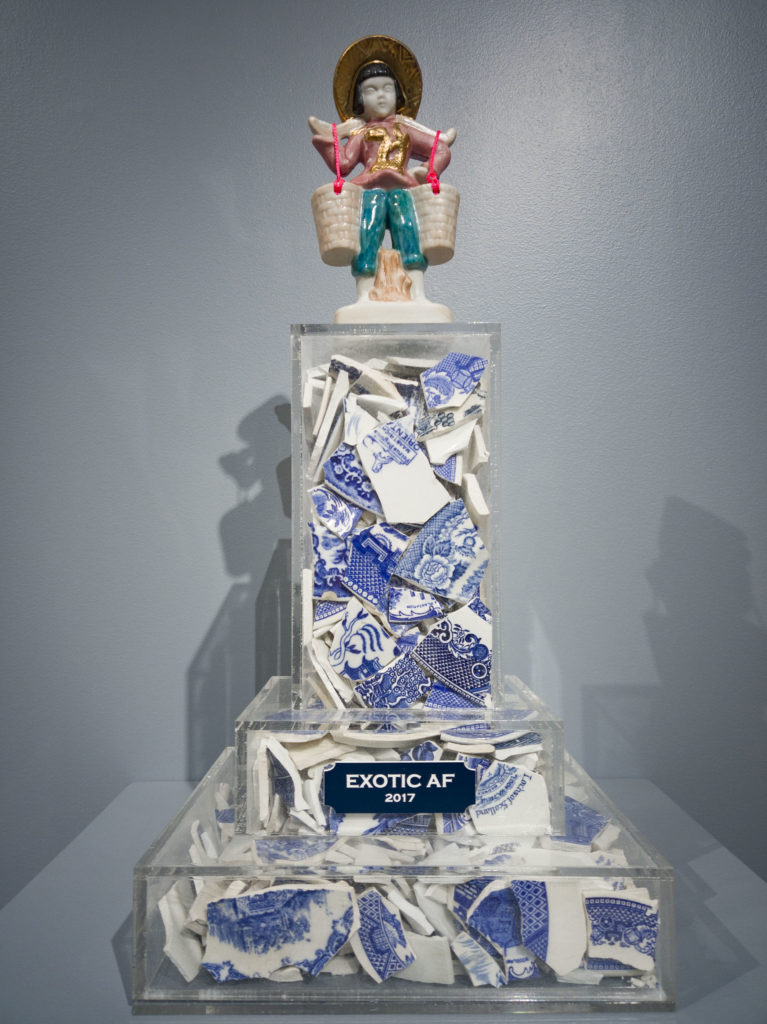

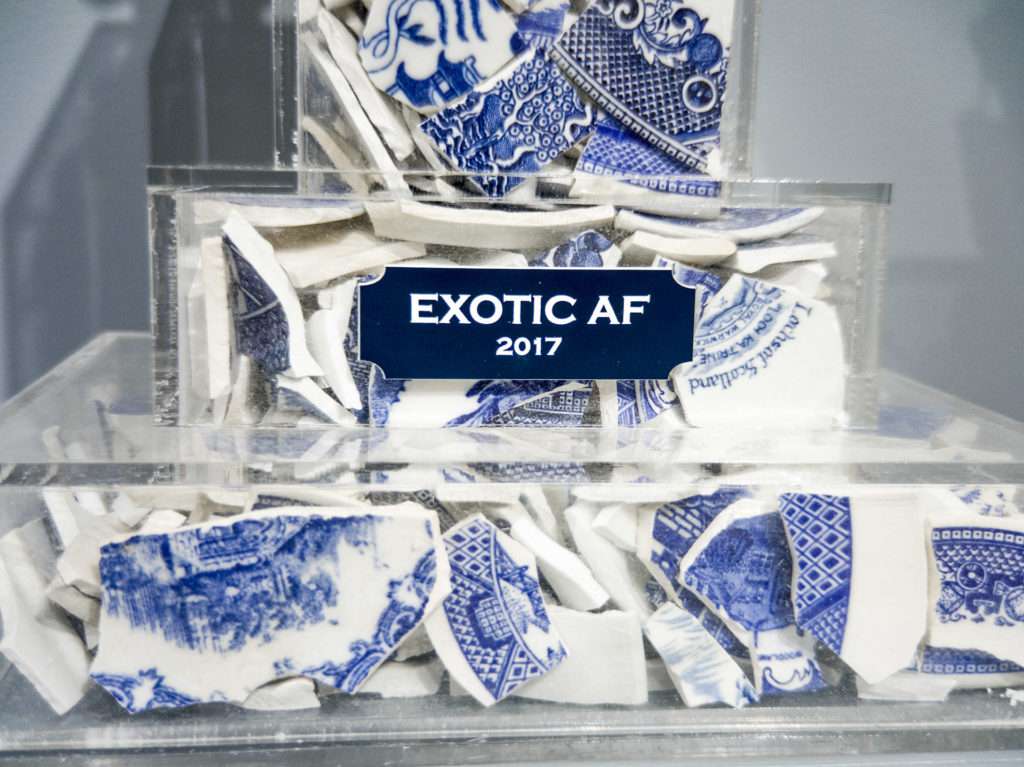

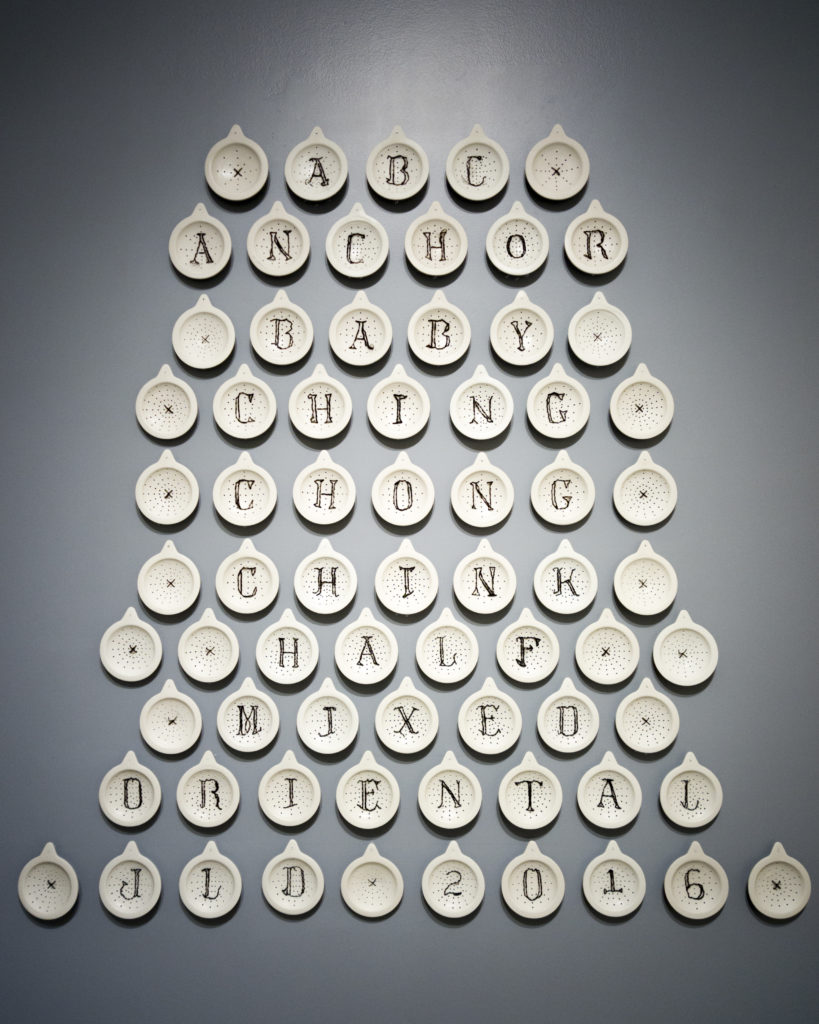

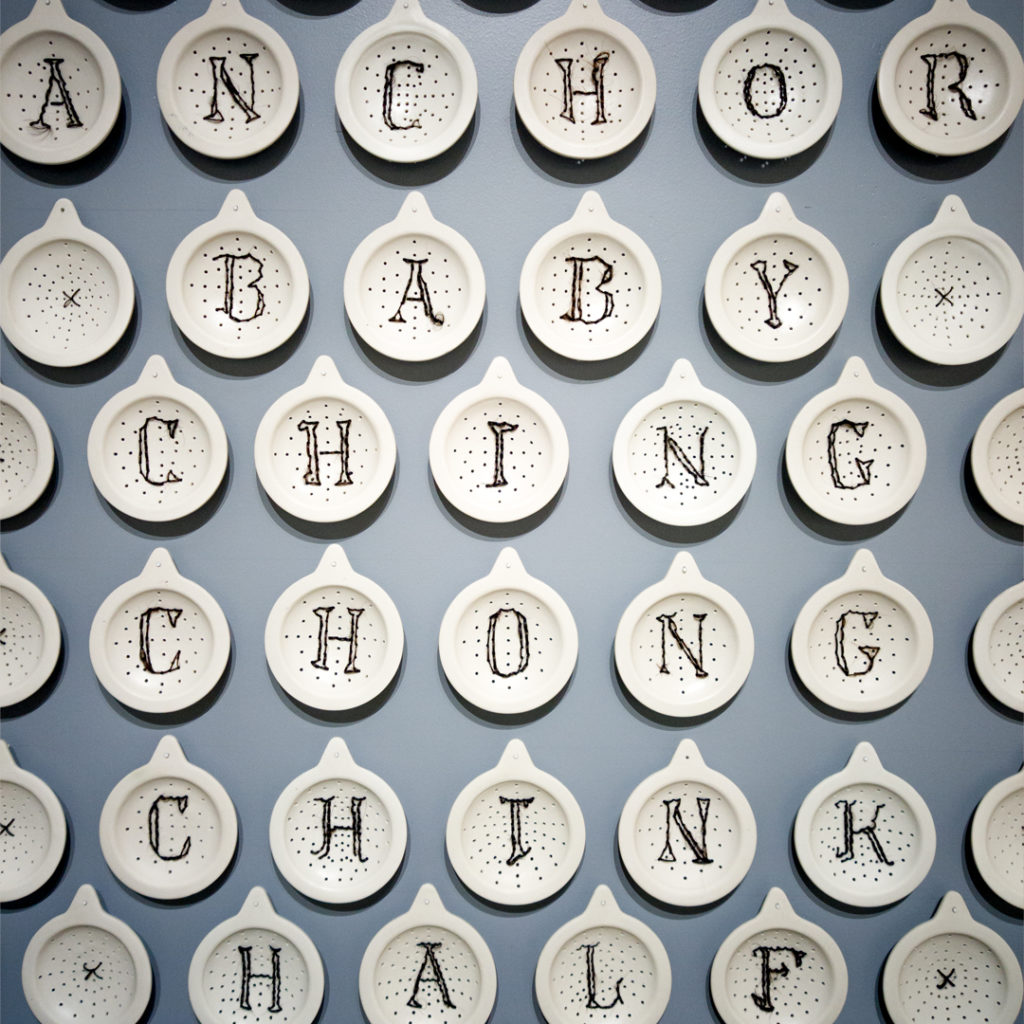

Jennifer Ling Datchuk

Jennifer Ling Datchuk was born in 1980 in Ohio and spent her childhood in Brooklyn, New York. Her mother immigrated from China a decade before her birth, and her father, a native Ohioan, was born to Russian and Irish immigrants. Datchuck holds a MFA from the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth and a BFA from Kent State University. She lives in San Antonio, Texas, where she is assistant professor of ceramics at Texas State University.

Datchuk refers to common domestic items and rituals in her work to address questions of identity, place, and belonging. She works with a variety of materials, including porcelain, fabric, thread, and hair. The Girl You Can series, which emerged from a residency in Germany in 2016 and coincided with the presidential election in the U.S. This series reflected her feelings that the country was growing more divided in what embodies true American culture.

“My work has always dealt with identity, with the sense of being in-between, an imposter, neither fully Chinese nor Caucasian. I have learned to live with the constant question about my appearance: ‘What are you?’” —Jennifer Datchuk

Jennifer Ling Datchuk, “Whitewash,” 2017. Video. Courtesy of the artist.

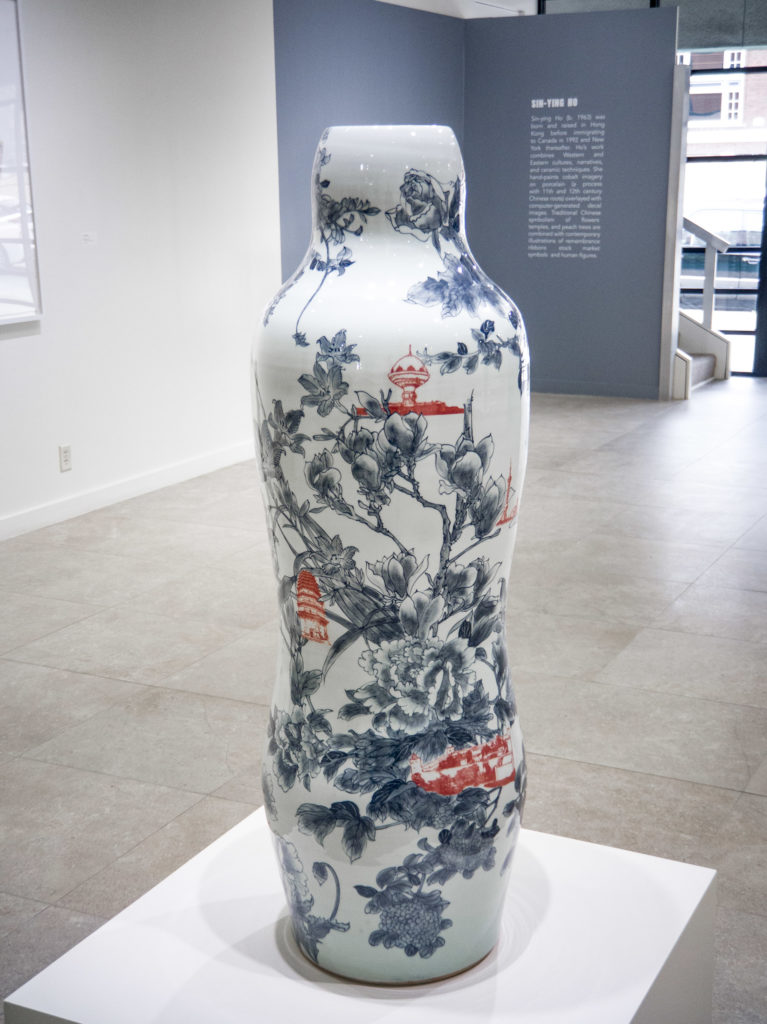

Sin-ying Ho

Sin-ying Ho was born in 1963 in Hong Kong. In 1992, she emigrated to Canada to pursue a career in acting before pursuing two degrees in ceramics (a BFA from Nova Scotia School of Art and Design in Halifax, and a MFA from Sheridan College in Ontario). She spent time in Louisiana before joining Queens College, City University of New York as associate professor of Ceramics.

Ho’s work combines Western and Eastern cultures, narratives, and ceramic techniques. She hand-paints cobalt imagery on porcelain (a process with 11th and 12th century Chinese roots) overlayed with computer-generated decal images. Traditional Chinese symbolism of flowers, temples, and peach trees are combined with contemporary illustrations of remembrance ribbons, stock market symbols, and human figures.

“…Growing up [and emigrating from] a colony like Hong Kong generates a sense of displacement and involves a constant negotiation of my identity. As the world moves towards greater globalization, many nationalities and cultures will merge together and evolve into an unknown global culture. I [refer to] my own experience being Chinese and living in North America with the cultural collisions I have endured. This cross-cultural experience speaks to a universal phenomenon.” —Sin-ying Ho

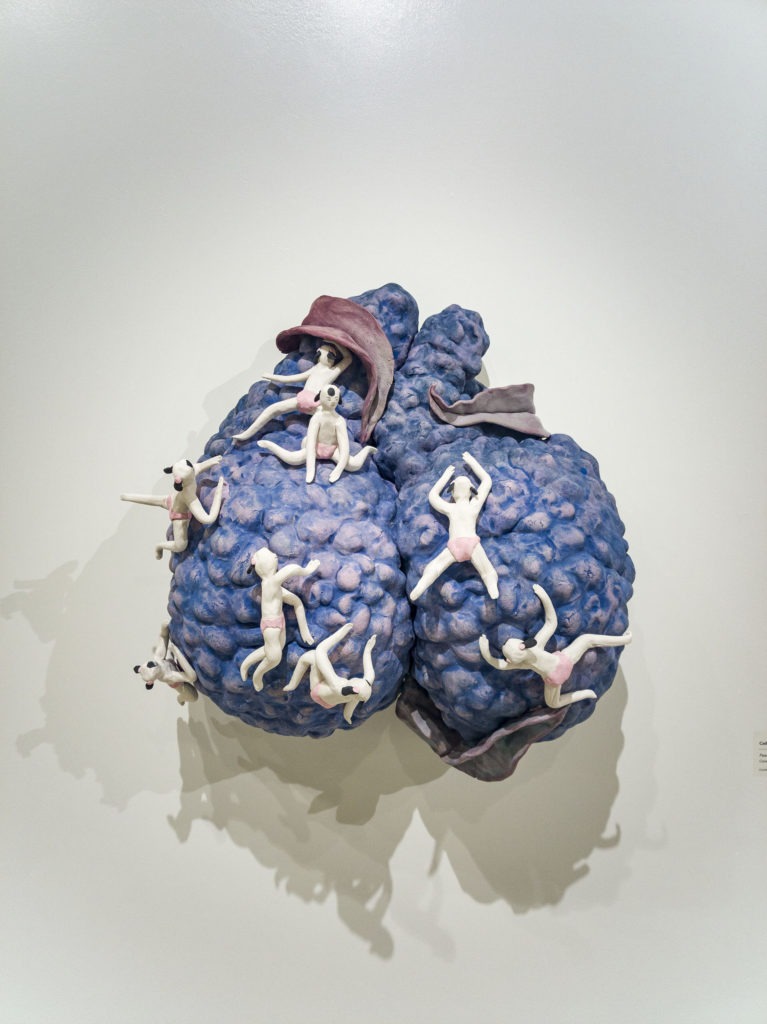

Beth Lo

Beth Lo was born in 1949 in Lafayette, Indiana shortly after her parents emigrated from China. She received a BA from the University of Michigan and a MFA from the University of Montana in the 1970’s where she studied with renowned ceramist Rudy Autio. When Autio retired in 1985, Lo succeeded him as professor of Ceramics, a position she holds to this day.

Water plays a central role in many of Lo’s works. In Flood, water takes the form of a blue-green celadon glaze found in the interior of each of the bucket forms. This glaze covers the lower-halves of the figures trapped in the buckets, each gazing upwards and on their toes as if they are trying to escape. Lo remarks that water symbolizes her frustration and alienation she experienced as a child.

Lo’s mother, Kiahsuang Shen Lo, a Chinese brush painter, was a long-time influence and occasional collaborator. Through her use of calligraphy and traditional Chinese forms and iconography, Lo examines the intersection of heritage, identity, motherhood, and language. Through her works, she attempts to reconcile the culture she was born into with her cultural heritage.

In addition to Lo’s studio practice, she illustrates children’s books and plays the bass and sings in multiple music ensembles.

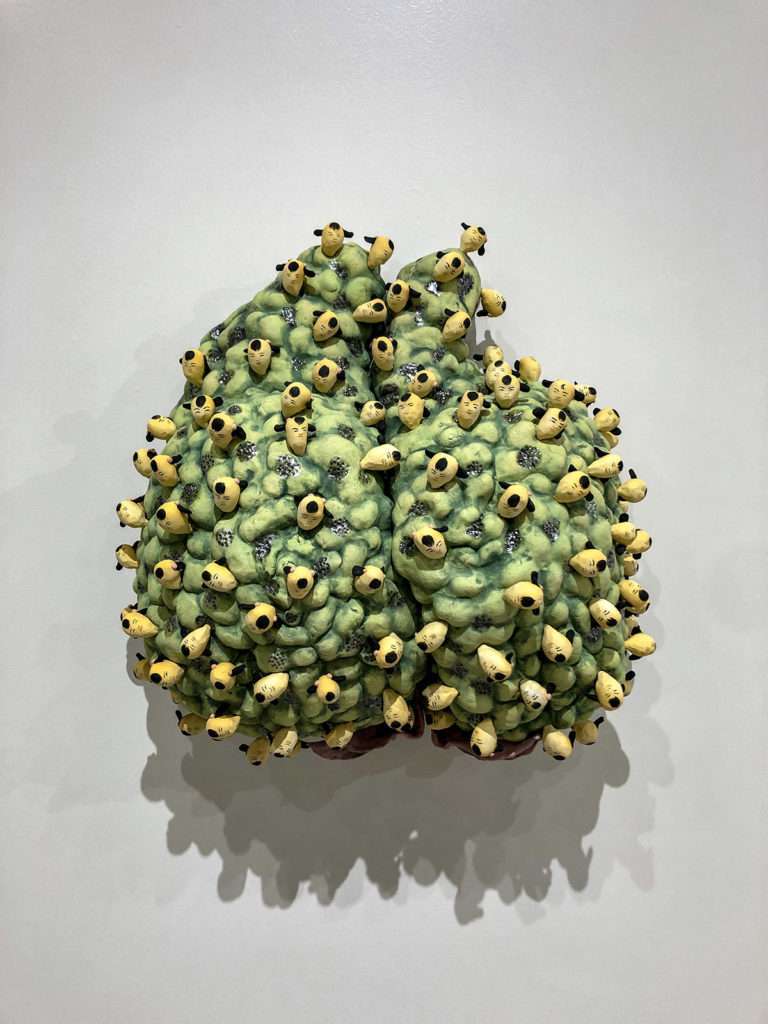

Cathy Lu

Cathy Lu was born in 1984 to, in her words, “the only Chinese American family in Miami, Florida in a neighborhood that was home to Cuban exiles and immigrants.” She holds a BA and BFA from Tufts University, and a MFA from San Francisco Art Institute. Since 2018, Lu has taught at Mills College in Oakland, California as assistant adjunct professor of Studio Art. She resides in the nearby city of Richmond.

Lu’s work explores the idea that food can be a language of “home,” creating a sense of identity and belonging. She enjoys merging Chinese and American food symbolism, and often uses peaches in her work. In Chinese culture and art, peaches symbolize longevity and perpetual vitality. In American culture, the peach represents femininity, as illustrated by the phrases, “you’re as sweet as a peach” or “Georgia peach.”

“I’m uncomfortable with the phrase Asian American because I’ve always felt that having been born here, I’m just ‘American’, but I understand that I will never be seen that way. I’ve always been surprised about how people react by the way I look – assuming that I can or can’t speak Chinese or English. If I’m in Noe Valley (San Francisco) washing my clothes at the laundromat, people will sometimes assume I work there.” – Cathy Lu

Stephanie H. Shih

Stephanie H. Shih was born in 1986 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Chinese-Taiwanese parents. She grew up in New Jersey before receiving her BS in Journalism from Boston University. Shih discovered ceramics and now works full-time as an artist in Brooklyn.

Shih explores concepts of home – not just as physical places, but also as cultural, generational, and emotional spaces. From afar, her installation work Pantry is populated by familiar asian household staples: Kikkoman soy sauce, Botan Rice, and Chinkiang vinegar. Closer inspection reveals the food labels, faithfully reproduced, are in-fact, “shakily painted” and “fingerprinted,” as if remembered in a distant, hazy memory. Shih engages with strangers through social media to discover and immortalize shared memories of growing up shopping at Chinatown grocery stores in the 1980’s.

“Food carries meaning for everyone but especially people who have only known life in the diaspora, whose identities are tied to a figurative homeland that exists only in the memories and experiences that this set of people have had.“ —Stephanie H. Shih

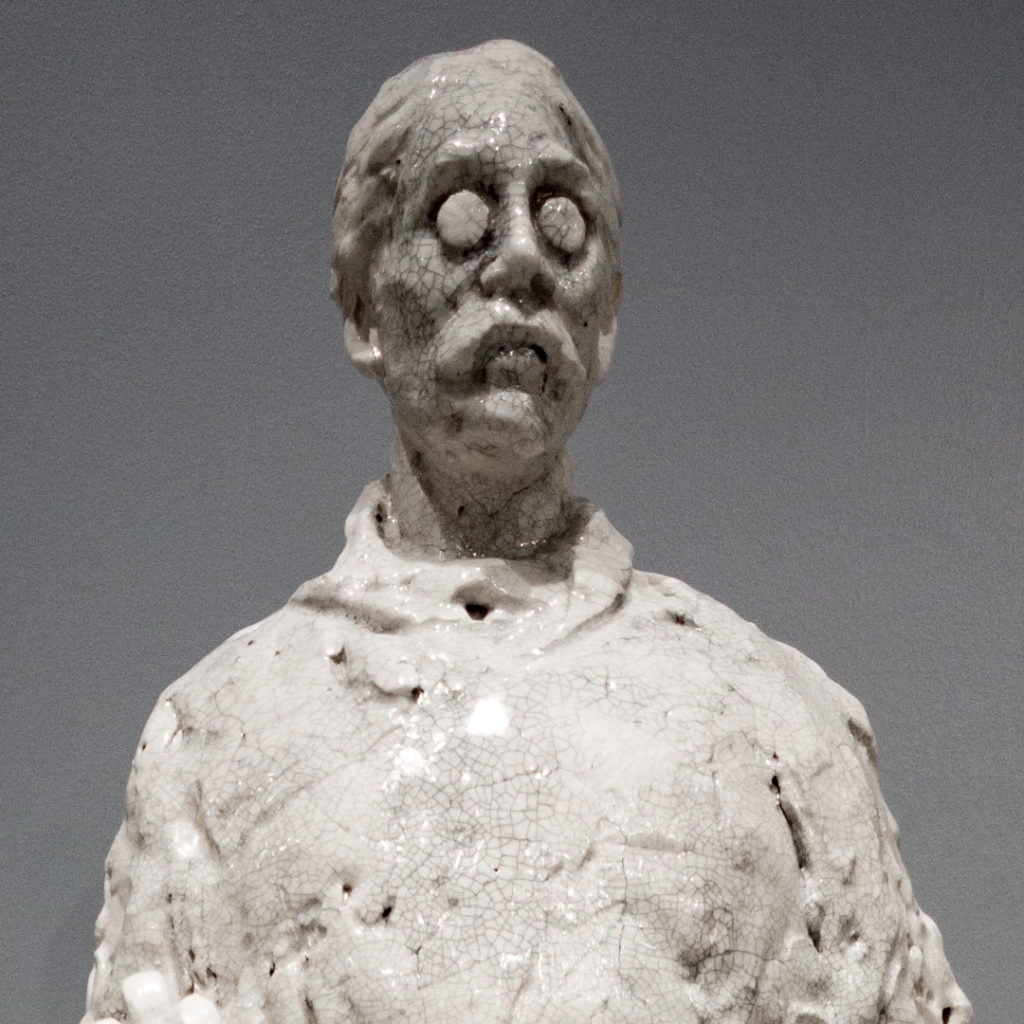

Wanxin Zhang

Wanxin Zhang was born in 1961 in Changchun, China. He received a BFA in Sculpture from Luxun Institute of Fine Art in China, before emigrating in 1992 to San Francisco. Zhang received a MFA from Academy of Art University, San Francisco, CA where he served as an instructor from 1996-2010. He is currently an instructor of sculpture and ceramics at San Francisco Art Institute.

Immediately after moving to the United States, Zhang immersed himself in the regional art scene of the San Francisco Bay Area. He cites Manuel Neri, Robert Arneson, and Viola Frey as his influences. As a result, Zhang’s work is a study of contrasting cultural influences and draws from both Chinese and American iconography. In Foggy (Horse), the sculpture is reminiscent of the historic terracotta warriors. In a nod to John Lennon’s iconic eyewear, the rider is wearing round spectacles as well as a backpack adorned with an American flag.

“As a Chinese person, clay is in my blood. Clay and ceramics have been an integral part of Chinese culture for millennia…At the same time, having distance from China is what freed me to utilize these materials to fit my personal narrative.” –Wanxin Zhang