November 12, 2005–February 4, 2006

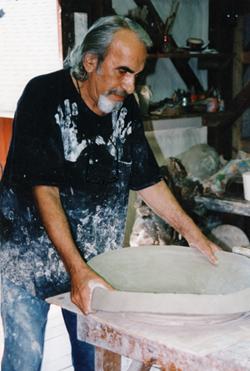

The American Museum of Ceramic Art is excited to present Peter Voulkos: Echoes of the Japanese Aesthetic, organized to honor the memory of Peter Voulkos (1924-2002) and to acknowledge his innovative body of ceramic work. Voulkos led the charge in the 1950s that altered the status of ceramics forever, shifting the perception of clay. Previously understood as a craft material suitable only for vessels, Voulkos reframed it as a medium appropriate for sculptural works of art. His break from tradition in pursuit of individual artistic expression has had an immeasurable impact on contemporary ceramics.

Though concentrating on Voulkos’s early work, Peter Voulkos: Echoes of the Japanese Aesthetic will include pieces from every decade of the artist’s ceramic production, concluding with massive pieces that exemplify the force of his mature work: “plates” pierced by slashes and randomly scorched by wood firings; “ice buckets” thickly constructed of rugged walls–crusty, raw, and cracked like the surface of the earth; and “stacks” assembled from multiple thrown forms, following a construct/destruct formula that includes torn, mashed, and hole-ridden surfaces.

It is well documented that during the 1950s Peter Voulkos, whether knowingly or unknowingly, took inspiration from a multitude of sources: abstract expressionist painting, Pablo Picasso, Julio González, assemblage-style sculpture, improvisational jazz, and African and pre-Columbian art. Included in the list of stimuli is the influence of Japanese aesthetics. From red clay Haniwa grave figures to quiet, unaffected tea ware; from calligraphic brushwork to raw Shigaraki-and Bizen-like surfaces; and from Anagama wood firings to natural ash glazes, there are many parallels between Voulkos’s work and the history of Japanese ceramics. Other factors include the impact of post-war revivalist folk pottery and Voulkos’s adoption of a “Zen-like” philosophy toward creative expression. Museum visitors will be able to compare Japanese ceramics and Voulkos’s work, prompting conjecture as to what role this artistic viewpoint may have played in the development of Voulkos’s style.

Our Voulkos story begins at the Los Angeles County Art Institute (Otis) in the mid 50s, where Peter Voulkos, newly hired to teach ceramics, adopted a unique classroom style. Working side by side with his students, “instruction” was described as osmotic, in direct opposition to the pedantic approach followed by many established instructors of the day. The pervasive spirit of the Otis group was one of creative spontaneity. Following Voulkos’s lead, this small group of students looked to many outside sources for creative inspiration, including post-war Japanese ceramics. To use a buzzword of the day, the students referred to the much-admired Eastern aesthetic as “Zen.” This word came to signify the state of mind that eliminated calculated moves and instead responded to the medium itself with an all-inclusive acceptance of the end result. Paul Soldner, the first of Voulkos’s students, remembers, “We didn’t study ‘Zen’ in a professional way–we joked a lot about it. Rather than knowing exactly what you were doing, you were encouraged to let it happen and learn from that. [Zen] was almost an excuse to free yourself.”

Whether seen in person or experienced through photographs, Voulkos was quite familiar with the ceramic works created after World War II by the Momoyama revivalists and the Mingei resurrectionists who rejuvenated interest in the folk pottery traditions of 16th century Japan. Japanese ceramics, including tea bowls, incense containers, flower vases, and water jars–shaped by the unaffected hand of the potter, marked by the capriciousness of fire, or characterized by loose brush strokes–will be shown in juxtaposition with Voulkos’s work.

Even beyond the Otis years, creative spontaneity, as inspired by Japanese pottery and Zen attitudes, touched the life and art of Peter Voulkos. In 1978, Voulkos met Peter Callas who subsequently invited him to fire work in his Japanese-style anagama kiln. This invitation led to a change in Voulkos’s firing preference, turning from gas-fueled firings to focus on wood-fired ware, the latter became his new standard. In 1983, Voulkos made his first of four trips to Japan. In 1995, Voulkos was invited to conduct a workshop at the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park where he constructed a number of platters that were later fired in a wood-firing anagama kiln. At this juncture in his life, one might hypothesize that Voulkos’s visits to Japan were not about embracing Japanese aesthetics, but the reverse. The curiosity was on the part of the Japanese.

For those who knew Peter Voulkos, it is difficult to describe him as anything but spontaneous. As an artist, be the medium paint, clay, bronze, or flamenco guitar, Voulkos pursued artistic expressions that thrived on improvisation. Peter Voulkos: Echoes of the Japanese Aesthetic will present an opportunity to reflect on Voulkos’s incredible ability to extract inspiration, absorb information, and reformat ideas in order to produce wholly unique work.

\

\