April 9–July 2, 2005

It is said that the whole history of ceramics may be understood through the study of the Chinese civilization. China, with its long, virtually uninterrupted continuity of some four thousand years, possesses in its archeological holdings and notable collections a complete timeline of the most vital techniques and developments in the field of ceramics. Confining this theme to one particular dynasty and, even further, to one region and time period within that dynasty, The Iron Saga will focus on the Southern region of the Song Dynasty.

The Song Dynasty is often referred to as China’s Classical period, an era famous for culture, literature, and the arts. In general, the ceramic production of the Song stands out because of its elegant simplicity. When compared to earlier pottery, which was quite basic and unsophisticated, or to excessively-decorated later ware, pots produced during the Song dynasty relied on design elements such as form, color, and texture for effect. The finest potteries were classified as Imperial kiln sites, devoted to producing official ware for the Court, while other sites were known for their “folk” art pieces, made for general use or exportation.

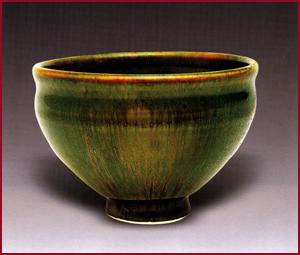

Several kiln sites located in the Fujian province of China, where the region’s finest white tea leaves were grown, generated bowls for the purpose of drinking this legendary beverage. Called Jian Yao bowls, they were made of hastily shaped course stoneware and glazed with thick, runny, brown or black glazes, perfectly colored to show off the white frothy tea. The bowls were fired in a wood-fueled hillside kiln. In their day, the bowls were considered common and not worthy of high esteem. They are characterized by the subtle effects that they show, such as brown or gold streaking referred to as “partridge feathers” or “hare’s fur,” or the clusters of iron crystals that leave “oil spots” glowing iridescently on the surface. As the glazes melt during the firing, the bottoms of the bowls fill with the fluid glazes to produce deep blue-black or golden-brown pools. Lost for centuries, the formulas and firing techniques used to produce these rare glaze effects have recently been researched and resurrected.

An interesting story explains how these humble bowls of China were transformed into revered treasures of Japan. Early in the 13th century, a Japanese Zen priest visited a mountain monastery in southeast China where he participated in a tea ceremony along with the Buddhist monks who lived there. When the priest returned to Japan, where tea rituals were also important tools of meditation, he brought a Jian bowl with him. Thereafter, these unassuming tea bowls came to be known as temmoku, a Japanese version of the Chinese Tien Mu Shan (Mt. Eye of Heaven), after the name of the mountain peak from which the newly respected clay cups originated. Today, the term temmoku describes a wide and varied range of iron-saturated glazes, each distinguished by the special effects produced when the glaze is applied thickly to a vitreous body, fired to the right temperature in the proper atmosphere, and with controlled cooling.

The Iron Saga includes a 1000-year-old Chinese tea bowl collection, exposing the ancient techniques of the iron-saturated glazes. Also exhibited are a number of ceramic vessels recovered from shipwrecks in the Philippines, dating from the Song to the Ming Dynasties. Visitors will be able to view these archeological finds as they relate to the story of iron glazes.

The Iron Saga, Part I: The Secret of the Song Dynasty

April 9–May 7, 2005

The Secret of the Song Dynasty will include a spectacular selection of contemporary temmoku-inspired work by San Diego potter Chun Wen Wang. In China, Wang is a highly acclaimed glaze expert, serving as a visiting scholar to the National Palace Museum, a visiting professor to the Luxun Academy of Fine Arts, and an independent consultant serving the ceramic industry. His ceramics are in the permanent collections of such prestigious national museums as the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC; the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco; the Cleveland Museum of Art; and international museums, including the British Museum in London. His works are also in many Chinese museums including the Taipei Cultural Center Museum, the National Museum of History in Taipei, The Chinese Museum of Hong Kong Art Museum, and the Long Quan Museum. His catalogue raisonné, Beyond The T’ien Mu Shan: Ceramic Art of Chun Wen Wang, was written in both Chinese and English and published by Wushing Books.

After many years of cone 10 glaze research, Wang began to focus on the lost Jian Yohen glazes of the Song dynasty. With American technology, he was able to take his research to a high level of excellence. Among his many glaze variations are those described as “liquid into liquid,” resembling the ancient “oil spot” but further ornamented or encircled by gold, silver, or iridescent rings. His palette is dramatic, with titanium gold iron spot and iron red glazes.

The Iron Saga, Part II: Elusive Glazes: Mel Jacobson and Joe Koons

May 14–July 2, 2005

Elusive Glazes will highlight fine examples from the brown-and-black-glazed ceramics of Mel Jacobson and Joe Koons. This section of the exhibition will present replications of the Chinese Song dynasty glazes that have not been exhibited in almost a century. To date, only three known examples of original yohen temmoku survive in Japanese collections. Thanks to the exhaustive investigation and experimentation carried out by Jacobson and Koons, AMOCA is very fortunate to have dozens of examples of this glazing revival, representing decades of research.

Mel Jacobson has spent his entire professional career teaching ceramics and making pots. He has, for the past few years, traveled across the United States, extending his ceramic techniques far and wide. He was named one of the outstanding ceramic educators in America by New York University and Studio Potter magazine and has written extensively in Ceramics Monthly, Clay Times, and Pottery Making Illustrated. A major article on his study with Joe Koons of temmoku Chinese glazes appears in Ceramics Monthly‘s March 2005 edition. His book Pottery: A Life, A Lifetime is an instructional narrative with full color reproductions representing the variations of his glazes. It was published in 2004 by the American Ceramic Society.

Joe Koons has worked in sales and has been the senior technical advisor for Laguna Clay Company for the past decade. He has spent a lifetime working with glazes at various temperatures and, for a twelve-year period, researched glaze effects for his own tile manufacturing. This work included color matching for field tile, decos, and murals. His tile works can be found at Circuit City, Vons Pavilion, and many other commercial ventures. He is widely recognized for his contribution to the restoration of tile at the historic Mission Inn in Riverside, CA.

Koons has a keen interest in Asian art and ceramic history, especially in ancient Chinese glazes. Combining a lifetime of experimentation, Mel Jacobson and Joe Koons have concentrated specifically on the current Chinese glaze project for over a year, and together they have unlocked the door to the ancient technique of yohen temmoku.